Ikawa Lab/Bioinformatics Center Department of Experimental Genome Research

In the past, animals harboring natural mutations have been used to elucidate the mechanisms underlying various diseases.

In the “post-genome project era,” genetically modified animals play a key role in basic molecular biological investigations and act as models of human disease. Our laboratory studies the mechanisms underlying mammalian reproductive systems through genetic manipulation of animal models.

Alalysis of molecular mechanisms involved in mammalian reproduction

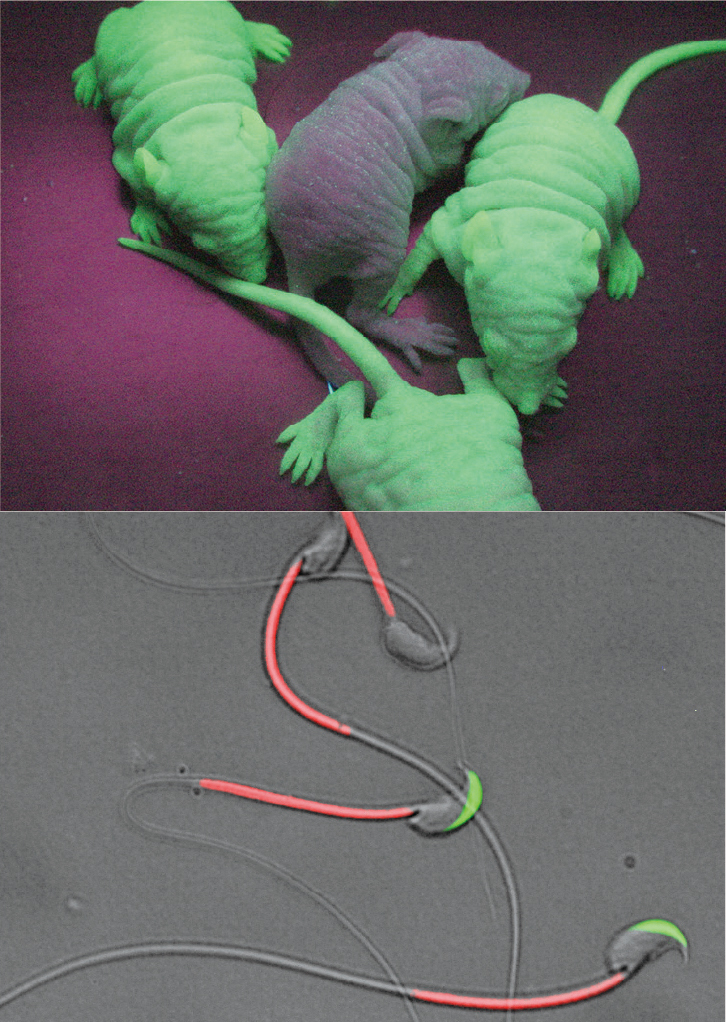

Our laboratory focuses to mechanistically study the mammalian reproduction system in vivo using gene-manipulated animals. We were the first laboratory in the world to produce genetically modified mice that express a green fluorescent protein (GFP) throughout the body (Fig. 1).

These green fluorescent mice are useful for many types of research projects. Indeed, we used these animals to label sperm with a fluorescent protein and visualized the fertilization process (Exp Anim. 2010; JCS. 2010, 2012; PNAS. 2012, 2013) (Fig. 2)

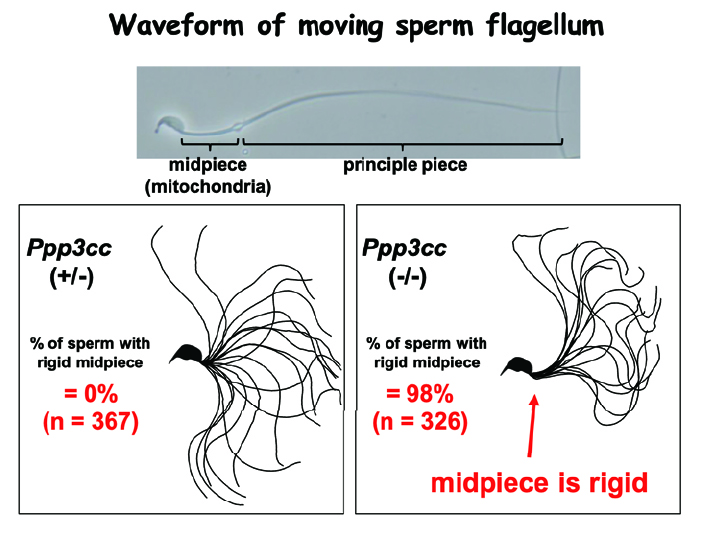

We introduced the cutting edge CRISPR/Cas9 system and have been improving the technology (SciRep. 2013, 2016; Science 2018). By utilizing the system, we have recently elucidated the lumicrine system; testis derived NELL2 go through the male reproductive tract's luminal space and triggers differentiation of epididymal epithelial cells through ROS1 receptor kinase. Then, activated epididymal cells secrets OVCH2 protease that modulate sperm fertilizing ability by trimming sperm membrane ADAM3 protein (Publication 3). We also found that sperm calcineurin (PPP3CC/PPP3R2) is essential for sperm motility and male fertility (publication 6). Inhibiting sperm calcineurin may lead to the development of a reversible male contraceptive.

More recently, besides IZUMO1 (Nature 2005), we found novel sperm proteins essential for the sperm-oocyte fusion process (Publications 4 and 5). Our laboratory will continue elucidating the mammalian fertilization mechanism.

Development of new technologies for producing genetically modified animals

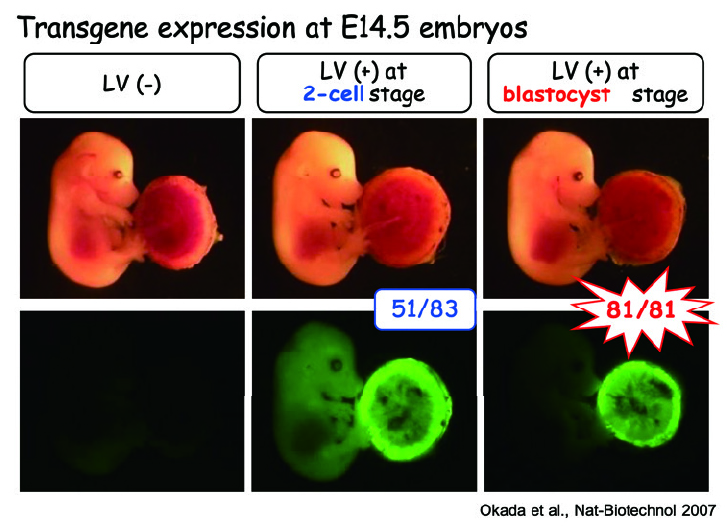

We are also developing new reproductive research tools and assisted reproductive technologies using various viral vectors and tissue culture chips.

For example, we have successfully developed a mouse model of preeclampsia by genetically modifying only the placenta using a lentiviral vector. Recently, we have also been conducting research utilizing the advantage of transient gene expression by using adenoviral vectors and LNP (Lipid NanoParticle). Additionally, by combining gas-permeable membranes and porous membranes to culture testes, we have successfully reproduced and observed spermatogenesis in vitro. Recently, we have also reproduced the implantation in vitro. By combining these techniques, we aim to elucidate mechanisms of reproduction and develop assisted reproductive technologies.

Our laboratory and the Animal Resource Center for Infectious Diseases support services such as the generation of genetically modified animals, in vitro fertilization, and cryopreservation of mouse strains.

For more information about our research and services, please visit our homepage (https://egr.biken.osaka-u.ac.jp/).

-

Fig. 1. GFP-expressing mice. Our “Green mice” have been used for more than hundreds of researchers and are good models for studying human disease (FEBS Lett 1997;407:313-319). Fig. 2. RBGS sperm. Transgenic spermatozoa carrying GFP and dDsRed2 in their acrosome and mitochondria. These gametes are useful to visualize the fertilization process (Exp Anim 2010;59:105-107).

-

Fig. 3. Calcineurin deficient sperm. Serm calcineurin is required for sperm motility for successful fertilization (Science 2015;350:442-445).

-

Fig. 4. Lentirival vector-mediated transgenesis in mice. Lentiviral vectors are not able to transduce eggs with zona pellucida (ZP) (left). Without ZP, transductions of fertilized egg and blastocyst result in the whole transgenic (middle) and placenta-specific transgenic (right), respectively (Nat Biotechnol 2007;25:233-237).

Staff

- Prof.: Masahito Ikawa

- Assoc. Prof.: Haruhiko Miyata

- Asst. Prof.: Chihiro Emori

- Asst. Prof.: Daisuke Mashiko(concur.)

- Asst. Prof.: Yuki Hatanaka(concur.)

- SA Asst. Prof.: Rie Iida(concur.)

- SA Asst. Prof.: Yu Ishikawa

- SA Asst. Prof.: Shingo Tonai(concur.)

- Postdoc. : Seiya Oura

Website

Publications

1) TEX38 localizes ZDHHC19 to the plasma membrane and regulates sperm head morphogenesis in mice. Kaneda Y. et al., PNAS (2025) 10.1073/pnas.2417943122

2)A small secreted protein NICOL regulates lumicrine-mediated sperm maturation and male fertility. Kiyozumi D. et al., Nat. Commun. (2023) 10.1538/expanim.23-0055

3)TSKS localizes to nuage in spermatids and regulates cytoplasmic elimination during spermiation. Shimada K. et al., PNAS (2023) 10.1073/pnas.2221762120

4) 1700029I15Rik orchestrates the biosynthesis of acrosomal membrane proteins required for sperm–egg interaction. Lu Y. et al., PNAS (2023) 10.1073/pnas.2207263120

5) Testis-enriched ferlin, FER1L5, is required for Ca2+-activated acrosome reaction and male fertility. Morohoshi A. et al., Science Adv. (2023) 10.1126/sciadv.ade7607

6) Human sperm TMEM95 binds eggs and facilitates membrane fusion. Tang S., Lu Y. et al., PNAS (2022) 10.1073/pnas.2207805119

7)NELL2-mediated lumicrine signaling through OVCH2 is required for male fertility. Kiyozumi D. et al. Science. (2020) 10.1126/science.aay5134

8)Sperm calcineurin inhibition prevents mouse fertility with implications for male contraceptive. Miyata H. et al., Science. (2015) 10.1126/science.aad0836

- Home

- Laboratories

- Ikawa Lab